Voices behind the mirror

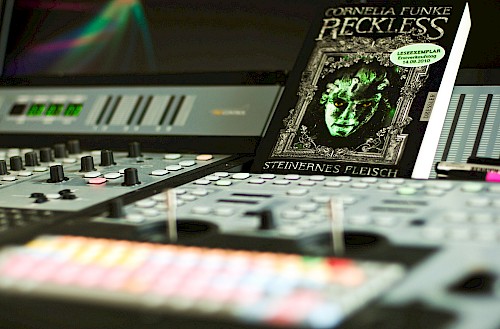

In June 2010, Rainer Strecker and the publishing company Oetinger recorded Cornelia’s new novel Reckless at a studio in Hamburg.

Behind the reflective pane is a small, almost empty room. It is filled with the voice of a man who is transmuting ... In June 2010, Rainer Strecker and the publishing company Oetinger recorded Cornelia’s new novel Reckless at a studio in Hamburg.

"Faster. He had to be faster." Closer and closer the pursuers came. Five of them, breathing down his neck, galloping after him. He pushes his gelding through a foaming brook, across mellow ground, a damp meadow, crouched down close to the horse's neck, his hood pulled far over his face. The hoofbeats reverberate from the canyon rocks, but he only hears his horse's snorting, feels a racking pain in his shoulder, that makes the world around him blur, feels the blood pumping in his throat, feels his haunters coming closer, sees them separating, sees them surrounding him, catching him — nearly — when the hood slips off his head and they see that he is not Will, but Jacob. Now, Jacob, they are going to shoot you, the Goyle's hate that you fueled will kill you. Jacob's hand reaches for the pistol, turned backwards he lifts his weapon, couches it and ...

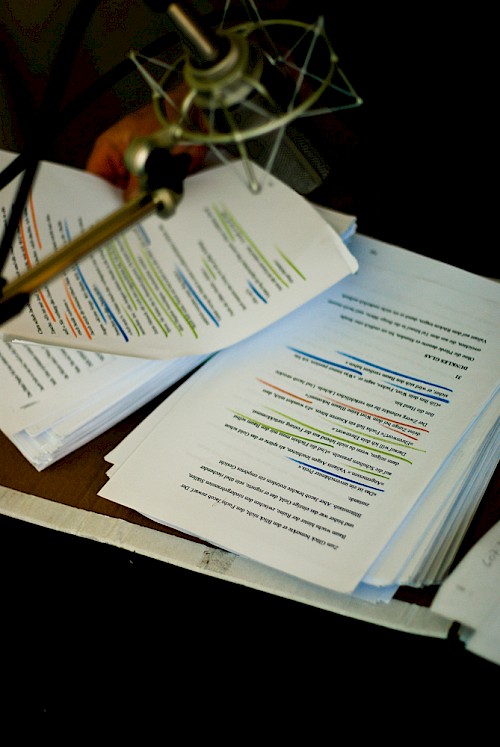

A hand is lifted, a hand holding a yellow ball pen and pushing a white button. "Rainer, that was fine, but a bit too fast, bit too fast." Markus Langer, producer of the Reckless audio recording, speaks into one of the control room's mikrophones. Vis-a-vis, behind a soundproof pane, Rainer Strecker looks up, nods in agreement and then turns to the text again. The text of "Reckless", printed on A4 sheets and marked in different colours.

He had been galloping through the lines, as if the Goyle were after him, putting spurs to his horse, putting all the haste, all the breathlessness, all the strain of close escape into the rhythm and sound of his voice, the voice that turned the chair he is sitting on into a horse, turned himself into Jacob Reckless and turned the small recording studio in Hamburg into a narrow gorge leading to the Valley of the Fairies. All this took shape, came alive, but just one tiny word made Rainer Strecker stumble — he has to read the passage again.

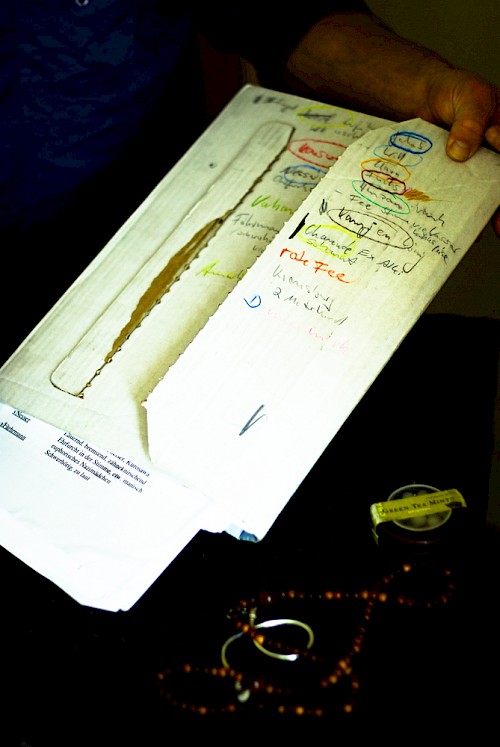

Time and time again this happens, once in a blue moon it works out right away, because turning a novel into an audio book is not as simple as just "Sit down, arrange a mike in front of you, start with the first and finish with the last sentence. Actually it goes like this: Rainer Strecker, Cornelia's German tongue, the actor who also read the German Inkworld audiobooks, puts a glass of warm water and a little tin of peppermints next to him. He takes off his wooden necklace — it could make a sound — , then pulls the manuscript out of a slipcase and looks for the next part to be read. Actually it is sentence by sentence, passage by passage, page by page. "We'd been up to make 60 pages a day," Markus Langer says, "but we get along even faster."

So, it is more simple after all? No, it isn't. Why not? Well, to answer this question you have to ask another one: What is a story? Apart from everything else, it is two things: first, it is a crowd of words on paper. Letters become words, words become sentences, sentences build passages and chapters. Second, it is much more than that, for out of all these words and sentences arises meaning — which often can be quite ambiguous. Atmosphere creeps, sensation pours, suspense jumps out of the narrative, catching the readers and listeners, surrounding and captivating them. When Jacob fights with the tailor, when he meets the Dark Fairy, when he sneaks into the Goyl City with snail slime rubbed under his nose, or when his brother Will turns page by page into stone: it's all just ink on paper — and at the same time so much more.

A sip of warm water, a few deep breaths, the jaws moving back and forth, unclenching the lips, expanding the chest, making the tongue roll in the mouth and so little by little acquiring a taste for the words. Like a musician tunes up an instrument, warms to it, slowly approaches the temperature of the tones and the flow of the tunes, Rainer approaches the story — and himself as the story's reader — at the beginning of each recording day anew.

In doing so, he is sitting in a "dead room". Dead, that's how the audio engineers call the small recording studio, a soundproof enclosure that makes all noises sound as neutral as possible. In a dead room a voice does not sound dull as it would do in an old mouldy library with thick curtains at the windows, and it does not echo as it would do in a tiled bathroom. It sounds like it sounds. It needs high effort to enable this. The table at which Rainer is sitting, does not have a simple wooden board, but upholstered in a foam-filled fabric. Moreover, there is a large number of expensive elaborate electronics and ten tons of bitumen. "This is a room-in-a-room-construction", explains Alex with his headphones sitting on only one ear. Alex Riess, the "sound guy", tells more about the room-in-a-room-construction. The recording studio's as well as the control room's inner walls are isolated from the house walls. It's the same with the flooring. It's like a cardboard within a cardboard, and in between the two cartons is a thick layer of, let's say, wool which secures that if someone knocks on the outer carton, not a sound gets through to the inner one.

Slowly, syllable by syllable, Rainer immerges into the Reckless world and yet has to stay at the surface of the words, has to control himself and his voice, must not be carried away by the story and yet must not be too afar, in order to combine both words and meaning into the vocal tone. That's the way to get through the sentences without stumbling, without harrumphs, hisses, gasps, spitting, swallowing, without 'um' and 'er', and yet not to sound as sober as reading the instruction manual for an electric toothbrush.

"Once again for the devices, please, then we can get started." Alex Riess has taken a seat in front of a desk abounding with a dizzying number of switches and keys. Rainer takes a deep breath. "And they'll live happily..." His voice arises from the speaker boxes; scarcely louder than a whisper it turns the words into a fraught, meaningful promise. "Fox jumped into the snow.... It took them two days to get back to the ruin, and at the carriage station..."

Arriving at the carriage station, Markus Langer pushes the white button again: "Naah/Nope, you still haven't got into the narrative mindset." The narrative mindset, the hold among the words, between the mere mechanical functioning of tongue and mouth and vocal cords and the not at all mechanical, the almost magical bringing to life of the story. "They had kidnapped the empress.", Rainer reads, and again that raises the question where to place the emphasis on: They had kidnapped the empress. Or had they kidnapped the empress?

Tough choice, and such choices have to be taken again and again. How should this or that text passage be interpreted. Which vocal tone will animate the written words in a way, that later on sense and meaning will immediately unfold and for the reader become comprehensible at first listening. So the meaning has to become clear. Clear, but not obtrusive. Finding this fine balance is the art of recording an audiobook: on the one hand, the art of the reader to get absorbed with a character only so far that he does not lose the perception of himself. On the other hand the art of listening and correction on the part of the audio direction team, to know when to interrupt the speaker and to know when interruption would distract the reader from the story's flow. Rainer, Markus and Alex make a good team: "Wills's voice was just a bit too high", Markus remarks after Alex has given him a hint, "that way it gets too close to Fox." So, once again.

The story's language is, as Rainer states, extremely compact, and passages have to be read several times until the complete meaning and diversity opens up. The text being read out, however, is easier to grasp. The words' importance gets more directly to the listener, is carried by the reader's voice, or rather his voices, for while reading he turns into many different characters, changes shape, colour, posture, mood, tone, rhythm, becomes Fox, becomes Goyle, Will, and Jacob, turns into Valiant the dwarf.

Rainer has highlighted each character in a different colour, has drawn blue and green and red and yellow marks between the lines. On the slipcase, wherein he keeps the Reckless script, he has written concise explanatory notes on each character's nature, terms like "with gritted teeth", "sober alky", "lurking, slowing down, with awe in his voice". He imagines the Fairy's talking like "coolish water, soft". His vocal tone switches from the high voiced, cautious Fox to the choked speech of Chanute, the innkeeper, whose voice is not loud, but so strained that his chest would unlikely be able to stretch and give space to air and words. The colours lead him through the text, through the constant shifting between characters.

Sitting there with the microphone close to his mouth, his only means of expression is his voice, one would suppose. But even reading is physical acting, it's a good deal more than just vocal interpretation. "I always use to read quite physical," Rainer says, "and that's reflected in my voice. I literally hunger for those tiny details that Cornelia places in the text, which give me indications of the character's physical appearance." So Rainer reads He imagines his ribs sticking together as his skin, stony like Goyle skin, can't stretch any further. He imagines an emotionless face, Donnersmarck's face. "What would someone be like, I imagine, who always furrows his brow, or someone who constantly presses his lips together, how would he sound like?" He sounds like Rainer sounds when he slips into Hentzau's skin, or when Kamien's temper takes possession of him. And what's more, a character may have a voice, but also many different moods, which in turn influence the voice. The voice has to change but yet stay the same.

With each sound, each gasp and hum and hiss and click coming from the voice behind the microphone, with every word — acorns, damp feathers, shots, cutters, Cudgel in the Sack and Little table, cover thyself! — the little green lights of the mixing console bounce and at high frequencies change into blinking orange. Markus Langer is sitting on his spinning-chair next to the desk and with concentrated attention, holding a ballpen between thumb and forefinger, he is setting the pace, as if trying to conduct Rainer through the sentences. "Go, Jacob.", it whispers out of the boxes. Breath caresses the syllables, hisses softly alongside the words, and 'yes, that was good, well read and well conducted. Markus' thumb goes up. Next passage.

Somehow apparitional Rainer appears behind the soundproof pane, that separates the control room from the recording studio, and almost, for a moment — Rainer just turning again into the excitedly gesturing dwarf Valiant — it seems as if he would be sitting in another world, as if his voice came out of another world, the other world in which he is sitting and reading and feeling: the world behind the mirror, the world, Cornelia takes us to, the world of Reckless.

Text and Photos: Michael Orth

No comments

Leave a comment