Interview Barry Cunningham

"My job is to represent children": Barry Cunningham, Cornelia’s British publisher, tells about his favourite books, about his polar she-bear, a secret passion and his work as a publisher. (The interview took place in summer 2016)

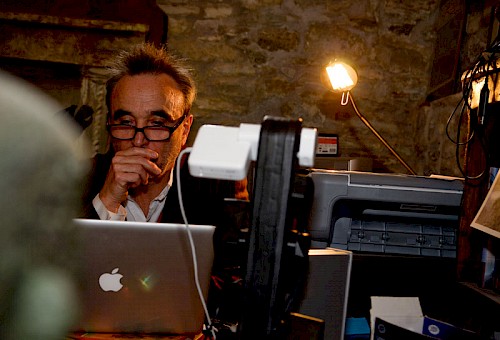

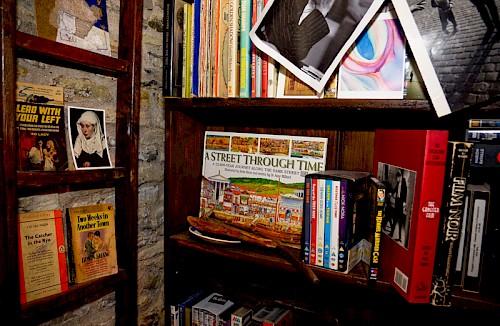

This is what it must look like after a museum, an antiquarian shop and a vinyl records shop exploded next door. Boom! Everything’s hurtling through the air ending up well-shuffled: in this room. Things are not just scattered around, they are literally surrounding you. No spare corner, always itching to touch this, to turn that, getting closer to take a look, coming within reach. Magnetised, engrossed – a plastic fairy, yellowed pages of old books in braided baskets, a small picture of a skull and a writing desk, that seems to be carpentered out of pirate ship’s planks. Natural stone walls and a plaster on the floor which has been trampled flat and greasy over centuries. Are we still in this world?

No, this is the study of Barry Cunningham, Cornelia’s British publisher AND – to say first things first – the man who gave Joanne K. Rowling the chance to let Harry Potter escape from his cupboard beneath the stairs into a published book. That was in 1997.

The entire house, a big, old one in a little village in Somerset, looks like this. Take, for example, the toilet door. You can’t close it. And behind this constant open door big Barack Obama is explaining the world to a dwarfish Queen. The scene can be spotted while having a pee: the president of the United States standing face to face with the Queen and a curious yellow submarine – natch, “We all live in....“ – is bubbling past the two. Those plastic figurines are lined up on a shelf opposite the toilet, like an Orc army. When stepping into the front hall, you are welcomed by a seven foot polar bear, stuffed, keep cool, it’s stuffed, while on the walls of the adjoining room some wooden masks are making scary faces.

What’s wrong with them? Don’t they like the Tibetan prayer flags?

Are they bugged out by Barry’s jukebox?

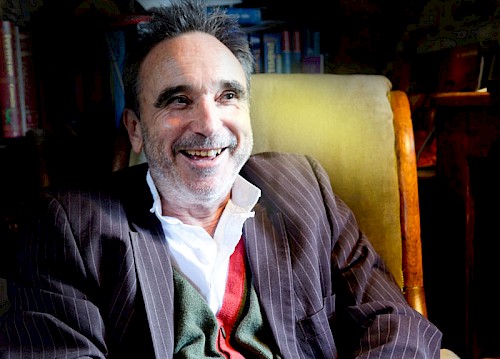

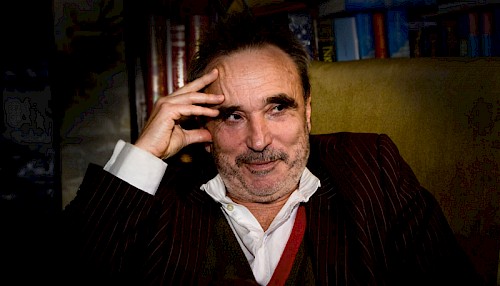

In the parallel universe of his study, Barry takes a seat in an armchair, which is kept from tipping by a book (what else?) put under one of its frail legs. A can of diet coke within reach, he crosses his legs and smiles ... as if there was a voice in the back of his head whispering that one may smile, because life, after all, is amusing. Well, this guy has named his publishing company Chicken House – since he has an old henhouse in his garden. So he’s the cock of the walk? No, he’s far too unpretending for that.

"Do you remember which was and which is now your favourite children's book?"

"Yes. When I was a little boy at school I was very bad at everything. I was not good at lessons, I stared out of the window – I could not learn stuff. And then I won a prize which in England they call a prize for merit. It means: They give you a prize just for trying hard. And that is the only thing I ever won. So they gave me a prize for trying hard, which is like you are really stupid but we know that you try."

He laughs – and tells of his life like telling a story he kind of likes. Listen carefully, but watch out: If you take him too seriously, you won’t understand him, and if you don’t take him seriously, you will understand him even less.

"I chose a book as my prize. I went to the bookstore and, yeah, at random really, I chose "The Hobbit". And I just loved it and then read "Lord of the Rings". But I always preferred "The Hobbit" because it was funnier and because it had a world which was full of heroes that were flawed – like me, good at trying, but not terrificly good at getting there."

He laughs again. Does he know that he could pass for a hobbit himself? Not exactly a beanpole, tousled hair, worn-out trainers, and so, gosh-darn it, unperilous and friendly. It did not even take five minutes of sitting together with one of the biggest publishers that one can’t help thinking of the word warmhearted.

"So, I love that book and I still got my copy. It was my favourite and my most influential book and I read it I don't know how many times, many, many times. I like it because it was a piece of domestic adventure which started from small things and it was very funny."

"Your favourite book of all? "The Hobbit" and "Lord of the Rings" are not only children's books specifically, but..."

"No, my favourite book of all is in the same kind of category, a book that children can enjoy as much as adults – like Cornelia's books as well. I think... "Treasure Island" is my favourite book."

Cautiously, softly, almost shyly, he gives this away, as if he was worried about offending all the many other books by his choice.

"And I love the bit when the pirate walks up those cobbles, and Jim hears him in bed, he hears him walking up the cobbles and banging on the door and it is a truly scary moment, but also it is a truly exciting moment. And then again I love it because it's funny, it's adventorous and – like in Cornelia's books – I love the villain. I love Long John Silver. But it needs... Today... If I were Robert Louis Stevenson's editor, here is a naughty thing to say: I would think the end is poor."

Laughter, a sip of diet coke

"I would have to send him back and say: This is a masterpiece, but, you know, the end just palls."

"When you were travelling with Roald Dahl back in the 1970s you said you learned the difference between what children really like and what they are told to like. By their parents or teachers for example. But is not the relationship between an author and a publisher quite similar? Let's imagine Stevenson says to you: This is my book, I like it the way I wrote it. And then you say: I like it as well, but the end is poor and you should write another end for me to publish the book."

"Well, I think today, and I think even then, an editor should be able to represent the readership. So, I am not saying that an editor knows the answers, but they should know the questions. They should say: Do you really think that's how this story finishes? Or do you think it carries on in a different way? I have never ever met a child who believes that the story finishes on the last page. And I have never ever met a child who does not imagine how the story goes on or how the story started before the first page. They are involved in everywhere the story goes, and where the author decides to stop it is very, very important. Stevenson decided to stop it there and I am not sure that's the right place to do it. That would be my question."

"So you think it is the decision of an author? Cornelia, for example, might tell something different. She says that she just looks for a way through or rather the one best way through the story, and that is how she would have to tell the story."

"I think, I think...

Pondering, gaining time.

My job is to find out what the best way is and to help the authors get the book on to the paper from the idea in their head. On a very ordinary level it's sometimes the question: Do you really think that makes sense or have you forgotten that the character has got pink trousers when he now hasn't. But on another level it is just saying: Where did you start that journey? Are you happy with where it has gone? My job is to ask all the questions, it's not to give an author the answers. But then again it is tempting to give the answers that I would like to see. My job is to represent children, so I have to ask questions. And often – not with Cornelia though – I feel that authors need these questions asked. It is a very emotional process.

Outside a horse is passing by, its hooves clacking on the pavement, followed closely by a group of noisy schoolchildren. They are carrying clipboards and pens. The horse starts feeling uncomfortable. It picks up the pace. Clipclopclipclopclipclop.

Very emotional, you know. Authors are not glad, particularly if a character is close to them, when you say: I don't really like that character. But, that's part of me, they would say. That is part of my personality, what do you mean, you do not like it? People sometimes said to Roald Dahl that his characters were really cruel and that adults were not that cruel to children. And Dahl would say: Some are. He always said it is his job to tell children not to trust anybody except themselves.

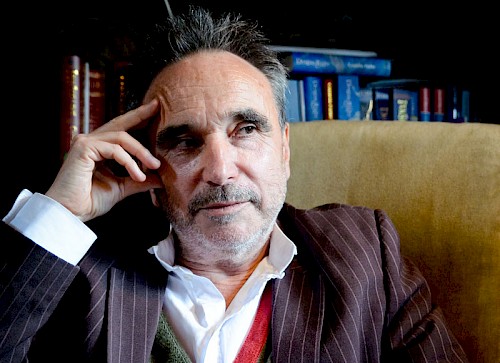

It is at this point that Barry sways his crossed leg’s foot for the first time, whereas his hands have been helping him all along. He likes to lay his finger on his temple, as though he could retrieve the answers there. Yet now his foot, for the very first time: to and fro, like a discreet gesture of recognition and respect for that stubborn, likeable curmudgeon that Dahl could be.

"Is there a special way or style of writing for children? Are there particular rules or conditions?"

"Adult writers come to writing for children in different ways, and it is a different process from writing for other adults. Because you are writing for people who are preparing the way that they look at life. They are growing and their experience is not so wide sometimes. That is why books are so precious to children and why Cornelia's fans have the books under their pillows. It is because she is showing them things that are very important to the way they think of themselves. That conversation can be like there is nobody else in the world. It is only Cornelia having that secret conversation with me. That is why she calls herself the secret friend of children. Because for them that's the only conversation sometimes they have, in their bed or on the bus or wherever. It is personal and it is for you and it is not about the television, it is not about an audience, not about a classroom. Just you. And that is why authors become so important to children. Because they are their secret friend, often they are the only friend."

And what about him, Barry? Is he the man, who quietly rejoices in sometimes paving the way for those friendships? It’s almost touching to hear him talk about children, who are just preparing for how to find their place in life. As though he tries to make it a bit easier for them by publishing books that tell them: You can do that, you will make it. Don’t lose heart!

"More often than not when I was with Cornelia or with Roald Dahl or JK Rowling children would say to them: Nobody said that to me before, nobody knew the truth about that, except you. And it's the same with teenage authors: Nobody dared say that. Nobody dared say you could hate your mother sometimes, nobody dared say I do not like it when you shout, nobody could say these things. Or when I am very, very scared of something, nobody could tell me, it is alright being scared. That is why publishing for children is so different from publishing for adults and why authors have a very different relationship to children than adults have to their adult readership."

Does he speak from his own experience? Little Barry, who learned only from books that it is okay if you are not good at school? Maybe. He didn’t have much time to get to know his father, who died of lung cancer when Barry was only six years old.

"I spent part of my life working with adult writers and adult audiences and they do not have this kind of connection. Their connection is not as emotional, not as committed and it is not as respectful."

"Do you remember when you were a child, I mean a real child, looking like one as well, did you think there were real persons behind the books?"

"The writers or the characters?"

"The writers."

"I suppose I didn't. Because in those days there was no way of imagining authors were real people. I always thought that they were part of the characters in the book. So I thought like Conan Doyle was a bit like Sherlock Holmes and I thought like Stevenson was a bit like Jim in "Treasure Island". No, I didn't think of authors as actually living beings, I thought Mark Twain must be like Tom Sawyer. I never thought there was someone you could email or rather in those days write a letter. I viewed them in the same fictional world as the books. But I have always preferred the fictional world to the real world or to what passes for the real world. Because all I got to remember was prizes for merrit in the real world whereas in the other world I was much better."

He laughs again. His fantasy leans over to the world of letters and stories, in which he is a dazzling, dragon-slying knight — or would he rather be a sage like Yoda? However, and that makes him so likeable, he doesn’t lose sight of the ’Real-World-Barry’. This man is kind of crazy, but far from being megalomaniac. The clicking noise of a can on the recorder – diet coke. And almost unnoticed: a lie? Not at all, just modesty, for actually the book prize is not the only recognition he gained in the “real“ world. In November 2010, the „Most Excellent Order of the British Empire“ was bestowed upon him at Buckingham Palace. By the way, that was one of the rare moments when he did not wear his brown pink stripe suit.

"You are often cited as being a child at heart. What are you in your head?"

"Complicated answer! I think childhood is a mental condition. And I think men are particularly good at not leaving it. It is what you might call sense of wonder or flow or whatever. I enter the experience of reading or listening to music, as if it is the only thing that's happening. And I don't worry, I don't put anything between those experiences and myself, I don't worry about the laundry or the profitability or my toe nails growing too long. For the moment when I am experiencing stuff, it is pure experience. I think humour is so important in children's books and you find children laughing when they are scared and crying when they are happy. And I cannot think that there is anything in life which is not essentially humorous. Life and death and everything else. That is the central portion of the child in me. I absolutely believe everything comes as part of something else. Like everything serious is funny as well, everything sad is funny as well, everything scary is funny as well. I think it is this state of mind that also is very important to my job."

He knows what he is talking about. When he was working for Penguin Books, it was part of his job to waddle through book fairs in a fat Puffin costume. Is that funny? Of course it is. If you take it too seriously, you will run the risk of believing you can fly and you will nosedive out of the window. He had a sense of humour about his bird appearances – just, as he claims, as he had about Harry Potter.

"Humour is why I bought "Harry Potter". In those days Fantasy was not really, well, known for its jokes. They took the whole thing so seriously, whereas "Harry Potter" is very funny. They laugh at danger, and that is an essential part of their bonding. If they did not laugh at the essential ludicrousness of danger, they would not be able to face up to danger. So that is the reason why I really liked and bought it. And that is also what Cornelia does and a lot of great children's literature does: using humour. Cornelia uses a lot of word jokes."

"As you claim to have learnt the difference between what children like and are told to like, what do you think they respond to and what are they told to like only?"

"They respond to a lot of different things. Like humour is an important one. I think they respond to as the single biggest thing...

Pause. Silence. Digging in the heart, searching, out and about in his child mind, throwing open sink doors, peeking in dark corners to find the biggest, the most important, the bee’s knees... And then: his silent rejoicing when he has found and said it, proudly but also modestly. A sense of modesty that comes from knowing that he has never lost his child-heart. It must be right. How else could he be such a joker and such a gentle, wise guy at the same time?

... adversity!“ It's what Roald Dahl used to call...

He starts imitating Dahl, in a loud, hoarse and emphatic voice, like banging that word against the bark of an old tree.

... valour! That's what my books are about, Barry, valour, being brave and true to yourself. And I think all children respond to overcoming adversity by being true to yourself. Thats the big thing. Struggle and misunderstanding is what they feel, and they respond to it deeply when other children oder heroes in a book are misunderstood, when they are pressed or taken advantage of and nevertheless stick to their true qualities and find a way through. Also they respond to animals. They have a so deep seated belief that we misunderstand animals and that all animals have secret lives. I have never met a child who does not believe that a duck or a dog has anything going which they are not telling us about. And children are interested in the physicalities of the world. I often say to people when they are beginning writing that they have got to tell what people look like, their physical attributes, and what they are eating. If you go to a phantasy world full of Gloops and Gurgons, you still want to know what they have for tea, because it is really interesting, you know, and important."

"You once said that children love books almost physically. What about you and your books?"

"I am not precious about them. I lose them, I give them away, I spill coffee on them. I prefer buying second hand books because I prefer buying books people have written in. I prefer seeing where it came from and I like it when they got like a sandwich stain on it or written in half a shopping list. So I am not precious about books. But I was a book hugger like you see them in Cornelias queues. Often you see little girls who are just hugging the book. Maybe that is like hugging Cornelia in a way. And they put books under their pillow. Cornelia has such a quote like putting the book under your pillow and the magic goes through your dreams. For children going to sleep, a book under the pillow certainly does do that."

"Getting to animals. You said you are a child at heart. You said that children love animals. So what is your favourite animal?"

"Well I used to say dogs because I thought I was a dog person but... I like dogs."

Barry’s dog is called Marley. He is a dark-coloured Tibetan, that has a charming way of laying his head on your knee to ’assist you with eating’ :) and to bark at you only five seconds later, because you did not cooperate.

"If it is pouring rain, and you say, well let's go and put the washing out, they would say 'Brillant idea! No one saw that, let's go and put the washing out! Let me go first. What a great idea!'

He is sitting there in his armchair, jolly as a dog, that is just about to be taken out for a walk in the rain. And you can trust that he would take his own dog out in the bad weather to peg out the washing. Just to have done it once. His voice almost flipped like a little Spaniel puppy which runs after a ball, trips over its own paws, becomes a ball itself and rolls over the lawn. Wow! I fell down and tumbled, did you see that? What a show! Where’s the ball?

"They are so optimistic, I love all that. But then I think I have grown up a little bit from there and I really like my cat Mabel now because the cat is more like: I am just going to hang out with you. I am just gonna be there and then I go again."

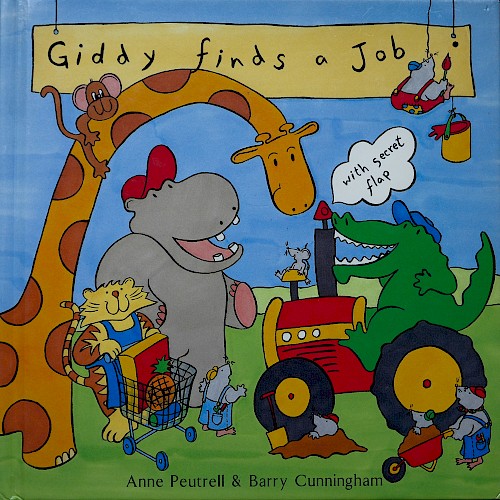

"But what about Giddy?"

"Giddy? Oh, Giddy, my giraffe! You know about Giddy! It is a secret. It is the only book I have ever written. "Giddy finds a Job". Yeah, its about a giraffe with a height problem. And as a giraffe I think it is really tough, if you haven't got the neck for it."

"If you could be a child for one day again, really, like after having ridden the merry go round in "The Thief Lord", what would you do? Where would you go? What would you eat?"

"Well, eating and drinking is easy really. I would go back and have my very first fish and chips, my very first fish and chips again. And I would have it with a drink called Tizer which I was never allowed, a very sugary, fizzy drink, a bit like Irn Bru. And then I'd have a whole pack of toffees all to myself. For I was never allowed more than one which pretty much made me sick. And then what I would do is... My dad died when I was very young – and he only ever did one thing that I would remember with me. He took me to Battersea Park fun fair and we spent the whole day at the fun fair and I made him go repeatedly down the waterchute. It was very high a waterchute and we got real wet and I made him do that again and again and again and we spent the whole day there and we got into big trouble when we came back and – I didn't know until two years later – that he had had a big quarrel with my mum and had just taken me off without saying where we were going. So it was a bad day, but I did not know it was a bad day. And I would go back and make it a good day. And I don't know if there is another thing I would want to go back again."

A trace of sadness. For he knows well that this is not possible. However, it does not mean he will stop dreaming about it.

"Can you remember what you wanted to become when you were a child?"

"By the time I was eight or nine I wanted to become an archeologist. I read this book about it and I thought you could dig through your back garden and find a Tutankhamun. It was just out there in suburban Reading. So I dug up a lot of things in the garden and I made a museum in my room with little labels like Piece of metal – could be from a Roman chariot. But then I found out that all having to do with science probably was boring stuff. That was when I wanted to become a journalist and then I wanted to become a rock star.

"But then you ended up as an archeologist nevertheless. For what you are doing is..."

"Yes, excavating. Interesting things from peoples minds. I'm digging out their thoughts."

"Imagine Mo from "Inkheart" would offer to read a character out of a book for you. Who would that be? Long John Silver?"

"Could be... Long John Silver."

He replies quite hesitantly. He is apparently not sure if that nasty pirate would scare him too much after all.

"Really? You would have to share your first fish and chips with him and maybe you would not get rid of him."

"But, no, no. Whom would I like, hm? Wait. What would I want him to read from a book into my life?"

He is perplexed, but at the same time thrilled by that imaginative possibility hovering in the air, which for him is no less real than his Diet Coke can.

"A character to come into my life? Wow. God. Well! It would be Cathy. From "Wuthering Heights". Or Becky Sharp from "Vanity Fair"?"

"First loves?"

"Yah, Cathy Earnshaw, Catherine from "Wuthering Heights", I have been deeply in love with for all my life. And Becky Sharp from "Vanity Fair", I think is just such a woman. Yep! But, no, I'd want Catherine from "Wuthering Heights", absolutely."

"Cathy!"

"Raw emotion! And she'd take me to that place in Wuthering Heights where she took Heathcliffe, which is the place where even in the summer in the moors there is still snow."

"Romantic thing?"

"Sounds a bit like it, doesn't it? I think we should pass on!"

It’s not that he is uncomfortable with it. It’s rather that his imagination already started carrying him into the moor with Cathy at his side. Surprising that he chooses such cunning female characters from century-old social tomes. Those Cathies and Beckies are not at all gentle lambs with which you are willing to share your toffee.

"What if it were the other way around? If Mo would read you into a book?"

"Such a good question. Where would I like to go?"

"To Cathy?"

"Oh, no, I don't think I should like to be in "Wuthering Heights". Where would I like to go?"

He furrows his brow, the wheels are spinning, the finger finds its place on his temple. Sitting crossed-legged in his old armchair, he is travelling through literary history in seconds. Short stop at the Victorian Age, a side trip to Fantasy? Not funny enough. American Realism? Certainly not. Maybe he would fit well in an early picaresque novel. Then suddenly, he arrives:

"Well, I see. To be honest: I would like to go to Hogwarts. I have spent quite a lot of time of my life talking about that so it would be quite good to go to Hogwarts, just as one of the guys in the back, that would be good."

"Even if you were not able to come back?"

"Yeah, I would be alright with that. Because I know a bit more about the story than anybody else. I took some chapters out of the first book, you know. So I could tell them one or two things that could have happened."

"If you had to leave the house now. For example like Meggie. When Dustfinger appears they would have to get away the next morning. Grab five things."

"Man!"

One minute he seems to be complaining about this unsolvable task, but the next he answers straightaway:

"My iPod, Im afraid. That would have to be, because it's all my music on it."

This man is a music maniac, fond of everything that’s making sounds. He has six children ... well, doubtlessly for some other reason. Yet beyond that: music. Beatles albums, shelves full of them, their empty sleeves hanging on the office walls, and if you would pile up all those CDs that are lying about in the kitchen, you could build a tower as big as Barry’s polar bear. After a short pause he names number two.

"A book called "Staying Alive", which is a poetry anthology and probably the best ever. Third would be the cat – we hang out well together. So, it's two more things to go. Hm."

There’s the "Hmm" he wasn’t in need of before. Followed by the utterly inconceivable. Something you would never think of considering theses battered Velcro trainers he is wearing right now. Maybe a hint to the wackiness, that crosses his nature from lower left to upper right, with his hair blown dry by the English wind and his pink-striped, single-breasted suit that clashes with the red border of his green cardigan. So, this is what he says:

"My pair of cowboy boots which I'm very fond of."

What an odd image, to picture him tucking his feet into a pair of crooked boots.

Isn’t he far too British to wear such John Wayne footwear?

"I'm very fond of these boots because, you know, they are very useful being in difficult situations."

What is he imagining? A 15 mile walk to the next service station after his car broke down? Or the invasion of an alien force, whose weapons pulverize those who aren’t wearing cowboy boots?

"Hm, fifth one. It's really hard, isn't it?"

"No."

"Oh as I would have to leave, I'd be taking the car. Car, cowboy boots, "Staying Alive", Mabel and my iPod. I think thats all you need."

"The car is already outside of the house, so the car does not count."

He raises his bushy eyebrows, trying to keep his cool. Actually he’d like to say ’Drat, I thought I got it, but now this annoying catch. Yet he keeps a civil tongue in his head and says:

"Car already outside, alright. Hm? Some diet coke? No. I'd take my polar bear. Not a diet coke, my polar bear!"

"Why is he so dirty?"

The bear in the front hall is wearing a ludicrous red fez askew on her formerly white head – at least one suspects that she once was white, because that’s what they look like, those polar bears on TV and at the zoo. This padded one, however, is brownish-grey, like an old bedroom window curtain that has been collecting the dirt and dust of a lived life.

"Well, he or rather she, for it is a lady actually, has been around for a while. I’ve had her since I was 21. She stood in a British confectionary company called Fox’s Glacier Mints. And when my sister asked what do you want for your 21st birthday, I said in a lighthearted way, I'd like a seven foot stuffed polar bear."

He says it lightheartedly as then.

"And thought nothing more of it. Until I got a seven foot stuffed polar bear, believe it, for my birthday. So I had her ever since. But I used to have a very small flat and I kept her with a sheet over her head. Here is the first time she's ever had enough room. But her paws are drying out, so I have to call a taxidermist to fix her. The British Natural History Museum once said I would have to put her in a bath to get her moist again, but, to be honest, I can't really think about getting upstairs and take her into the bath."

"And have a glass of champaign. Music. Candles."

"No, no. She's not that kind of bear."

"Is there a particular country or region in the world you would like to publish a book from?

"Lots of regions. I would like to find a childrens book from Japan that's not a Manga that I can publish. I'm so very interested in their storytelling. Also I have looked in several books from Africa written from an African point of view. I would like to publish things from a slightly different set of imagination. Books from Africa and India written in English tend to be about our shared experience mostly, it's all pretty much the same. But the stuff I read from Japan is so strange and so different that I would like to find some children's books from there. I'm interested in children's books from Brazil as well. Most of the books we publish in translation are from Germany or from France and a couple are from Holland."

He chokes back a snicker, as if that was kind of absurd. Well, it is, in a way. There’s a world full of books and stories and imagination, all different, all special, but many of them come from around the corner, culturally speaking.

"The Spanish have some great murder books, very violent murder books for teens and so do the French, but I haven't found a real great story yet. I think children do have more in common internationally than there are differences. So it should be possible to find more books to publish from around the world, but it is difficult because translations often are not very good. So it's mostly imagining what a good translation would be, like imagining a symphony from somebody whistling a bad version of the tune. It takes a great leap of faith to commission a book from Finnish, when you don't completely understand what's going on. Really difficult. But well, Japan fascinates me. The whole storytelling culture of Japan. It's partly a very fierce culture and the position of childhood seems to be slightly different. Which is interesting."

"You said Chicken House is about new authors, giving them a chance. Isn't it quirky that while books and stories are about open-mindedness, the book industry is a very self centered and closed world? When you say Chicken House wants to give a chance to new authors I think it may be to find a book to publish without paying the author much or as much as you would have to give to an already famous author. For the newby is happy that the story gets published at all."

"It's true. It's true. New talent always goes with bigger risks, but also goes with bigger returns. So it is a sensible thing for a little company to concentrate on. The rewards can be immense, but they can also be catastrophic. When new authors don’t turn out to be the talents you thought they would be, there is total failure. Whereas when you buy an existing author with a track record, it will not make so much money, but you won't lose so much money as well. It's an entrepreneurial area like new music: risks are higher, rewards are higher, because people will take less money for your higher risk on them. The risk for the authors is not very big. For us, the publisher, five or six books out of twenty may be a complete and utter failure, that's either due to bad judgement or bad timing. Like it's "Treasure Island", but we published it in the wrong century."

"Or with the wrong end. Isn't working with new people sometimes easier?"

"Never!"

He blurts out the answer even before the question was finished.

"When I worked for Penguin, 90 per cent of the books I bought were already published. You bought them from very little original publishers and the company was almost totally marketing driven. I was marketing director and almost totally what I thought was how we sell them, not if they were any good. It was how we position it, how we market it, how we prize it, what format we put it in. Which is a very difficult business in a different way, but not as interesting and not as creative, for you could not really alter the product that much. But with a brand new author it sometimes is also a difficult task. You may ask them things they can't do. And also maybe an author can only write one book. When I was in the music business very briefly, many people could only make one album, because they have been rehearsing it for ten years and they were incapable of making another album in the time scale they had to make it. So a lot of people are incapable of writing a second book quickly when they have spent ten years writing the first one. And nowadays you can't wait. If your second book does not come out after three or five years, then you know how forgotten you are. So: more risky but also more rewarding."

He sounds as if it was a big, exciting game, sometimes you win, sometimes you lose. Maybe that is the frugal serenity of one who often won, but has not yet forgotten that it’s all about taking pleasure in that game.

"Have you ever thought about publishing a book written by a child?"

"Yes, and we have done some work with children. To try and get them to finish their books. There was a girl who used to come regularly to Chicken House. She was the daughter of a shopkeeper down the road and she had great ideas in her stories and her writing was brillant and I kept encouraging her. I made her dad bring her in in the evening. But then she got a boyfriend and started going out, you know? I don't know, if children have enough perspective on their own lives really. Also many children haven't got a voice yet and when they write they often do so imitating other people's voices. It is interesting and at the same time a strange thing to think about that children's books are dominated by adults for children. And the whole industry is based on what we think children will like. However, I think I am a really good judge for that. And I think Cornelia probably finds I am quite a good judge. And also JK Rowling thinks so. I don't know if Roald Dahl used to think so."

Probably Dahl would agree, but wouldn’t put it that bluntly for one would run the risk of being taken for a softie. Something Barry is obviously not worried about at all. Ridiculous tattle. In the end, it’s because adulthood still does not hold him captive and, even if it sounds cliche, he is still a child at heart. He brings children’s interests to the point: secret wishes, feeling small, alone, self-conscious, misunderstood. Their will to discover and to persist. The way he puts it in words illuminates the uniqueness and importance of childhood – for children as well as for adults. And it illuminates his pleasure in discovering books, in allowing stories to grow and last but not least in publishing them.

"Thank you Barry.

Thank you very much."

"Welcome, welcome. Now come and have some lunch."

No comments

Leave a comment